WebVisCrawler: How I created an (I think) optimised web jumper in Python

It took me 35 hours to create the project and I finished it in 1 week total, that's like more a fifth of the week 💀

10/3/2025

From 1-7 September, I was working on a project called WebVisCrawler in Python. The idea behind it was to visualise the World Wide Web® as a graph of nodes. Not for any reason in particular, but because I thought it would be fun. It was, but it was also a lot of pain. You can see the demo on the link here. Unfortunately, the github repo has no history because I forgot to create one in the start, so you can only see the final product.

You might think, "well geez, a web crawler, like that's never been done before ya blithering idiot", and that's how I originally started this idea. I started off with what was effectively the most basic form of crawling you could get: a python script that looked like this:

url = "https://example.com"

links = [url]

while len(links) > 0:

current_url = links.pop(0)

page = requests.get(current_url)

soup = BeautifulSoup.parse(page)

for link in soup.find_all('a'):

print(f"Found url {url}")

links.append(href)

Async await hell

Seeing as one of our main problems is running requests synchronously, it would make sense to start by utilising coroutines and async/await space. By changing the code to use something like ClientSession(), we can create some async code that looks more like this:url = "https://example.com"

links = [url]

async def geturl(url):

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

async with session.get(url):

let data = await response.text()

let page = parse()

# then we find the links and keep going

async def main():

for link in links:

geturl(link)

asyncio.run(main())

Whether this was my fault (keep in mind the code above is NOT the real code) or the system's fault was unknown, although I will assume it was probably me. What I think was the issue was because of the parsing taking a while: parsing was most likely a CPU-bound task, and coroutines waiting for the parsing to continue would actually slow down the system even if other coroutines suspended while waiting for the network request to finish.

Multithreading should work then

So saying "screw it" to coroutines, I decided to use multithreading. After reading about some "GIL" and some other stuff that I didn't understand, I decided to just try it out. It was pretty much what you see above except with threading.Thread for each geturl call.Surprisingly, this did work pretty well. I started seeing more performance gains, and the amount of URLs processed per second increased decently. However, there were still a ton of issues, as seen in this bullet list below:

- Too many threads caused crashes

- Shared data structures weren't being locked to threads

- No way to visualise progress

- Some threads waited too long for dead URLs that softlocked the system

This built to the softlocking issue: if we set a limit of 512 threads, and 512 threads were all waiting for dead URLs, the entire program would softlock and never recover. This was a big issue, and I had to implement timeouts on requests to make sure that threads wouldn't wait forever.

The second issue was also a big one, but I didn't really realise it until later. In the meanwhile, I added some status updates, and also added locks to the shared data structures. This helped a lot, but there were still times where some threads would be waiting on requests, while other threads wouldn't get any new URLs and assume that the queue was empty.

With my current model, I also failed to accurately maintain a count of threads, which wouldn't end well.

Multiprocessing to the rescue?

After reading about the GIL as well, I realised that plain threads wouldn't cut it (get it???). The bigger issue was an issue with concurrency, but I don't realise that until later.So naively, I decided to try multiprocessing. This was a bit more difficult to set up, because unlike threads, processes don't share memory space, so I had to use multiprocessing.Manager to create shared data structures. This didn't seem to be an issue originally though, since I could just use the Manager's lists and dicts to keep track of everything like I did before.

I'm a blithering idiot

The unfortunate fact is that I learnt nothing from my Rust project. I still had no idea about concurrency,

race conditions, and all that jazz. multiprocessing.Manager was way too slow, and the performance ended up

worse than when I was using threads. I also had race conditions because if a process was getting a URL from the

queue and another process also got the same URL before the first process could remove it from the queue, both processes

would end up processing the same URL.

The unfortunate fact is that I learnt nothing from my Rust project. I still had no idea about concurrency,

race conditions, and all that jazz. multiprocessing.Manager was way too slow, and the performance ended up

worse than when I was using threads. I also had race conditions because if a process was getting a URL from the

queue and another process also got the same URL before the first process could remove it from the queue, both processes

would end up processing the same URL.

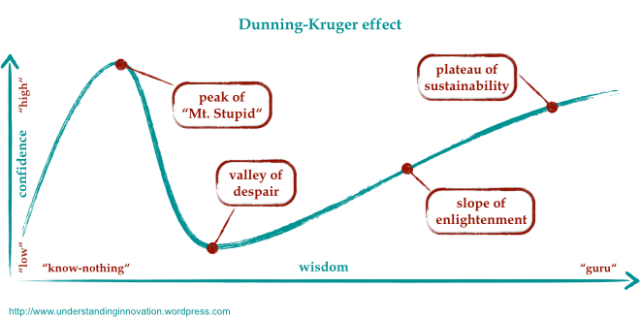

This is where I realised that I was at the valley of despair. You can actually see me giving up on this method in the website, where I only process 1 process and 2 processes.

When you hit rock bottom, though, the only place you can go is up. I decided to read more about multiprocessing, specifically about optimising Manager, when I saw this.

But assuming your actual worker function is more CPU-intensive than what you posted, you can achieve a great performance boost by using a multiprocessing.Queue instance instead of a managed queue instance. - BoobooEnlighted with the knowledge of Booboo (excellent username, by the way), I decided to get out of despair and find out what a Queue even was. After finding out that a Queue is a method of message passing for processes, I decided to optimise using Queues.

Understanding that every message sent through a Queue is expensive and is serialised, I decided to abstract the system into Manager and Process. The Manager would be responsible for keeping track of what URLs have been seen, what's going to be processed, and what has been processed. The Process, in turn, would get URLs from the Manager and return their status and what links they returned. This way, process communication is handled through a safe structure and since only our Manager controls what links are being processed, there are no more race conditions or double-processing of URLs.

Finally, I had one more big issue: memory usage. Keeping track of every URL seen was obviously a necessity, but storing every single URL in memory gets expensive over time. Going up to a max of 80k urls, the memory usage would be enough to completely crash my Mac!!!

I weighed my options: I was already keeping track of URLs in an adjacency file, which I dumped after 1000 URLs to save memory. All I needed was an accurate way of making sure I don't process a URL I've already processed. I could compare hashes, but computing and storing hashes would result in memory usage as well. I could use a Set, and I was, but Sets use way more memory than lists anyway. Then, I discovered the Bloom Filter, a probabilistic data structure that acts like a Set but uses way less memory at the cost of some false positives. After grabbing a Python package for a scalable Bloom Filter, I implemented it into the Manager, and finally, my memory usage was under control.

Mentioned literally everything but visualisation...

For visualisation, I... just asked GPT to throw me some ideas. My original idea was to have a desktop app that would process the adjacency list, but that would be easier said than done: I had no idea how to create an efficient graph visualiser that could handle thousands of nodes. So I just asked GPT to implement something fast, so it went with vis-network after calculating the edges for each node.I was able to add some more custom features to the visualiser and the generated page as well, like focusing, listing all connections, having different types of nodes, and filtering out specific types of nodes. It makes really cool graphs, if I do say so myself.

Results

Compared to my starting, the amount of URLs processed per second increased a lot. Each iteration of the program was able to bring some new idea to the table, and I was able to finally create a working web crawler that could process thousands of URLs in a reasonable amount of time without crashing my computer.You can see the results, but with 8 processes, I was able to process 5665 nodes in 18.26 seconds with 610% CPU usage. Not bad for a week's work, if I do say so myself. Oftentimes, the amount of nodes processed can reduce due to rate limiting, dead URLs, and other network issues, but overall, I'm pretty happy with how it turned out.

Compared to the original multiprocessing implemention without queues, a lot of URLs were skipped because of how long it took to process each URL. One 2-process run looked like this: 40.19s, 956 nodes, 1541 edges, while another looked like this: 37.63s, 2322 nodes, 3067 edges (exception in thread).

Learning about optimisation and concurrency was definitely a fun experience, and will definitely come in handy for some of my other projects (hopefully post coming soon!).